Filed under: opinion, personal essay, travel | Tags: 19th century, Business Mirror Philippines, cottage, dirndl skirts, farmers' makrets, French windows, pancakes, peregrine notes, Robert Frost, rocking chair, Shaftsbury, Wilmington Vermont

What legacies we carry hardly ever figure out in our daily lives with bequeathals like mansions and other such obvious signs of wealth being the exceptions, of course; more common to us, like mine, in varying degrees hardly overwhelm or glitter. Often summarized in a word as ‘values’, which may include status either inherited or earned by noble action, even a way of life, families are their innate source. I would add that learning either from school or one’s own pursuits broaden legacies, and even at times turn out as sources of more priceless legacies like history as well as peace and beauty in landscapes from travels, that ironically for most, are often less valued for their amorphous nature.

Such peregrinations wouldn’t have fallen on me had I not traveled to Vermont farther north of New York last month. Or again, I didn’t count on it, expecting instead, endless romps on green meadows that the Green Mountains let nestle on their bosom. Would but Nature was all I dwelt on: cloud shapes like grazing sheep on cheeks, mountain mist on waist of giant fir descending in diaphanous calm, expansive skies as if eternity were within one’s tipped toes.

But haven’t I viewed my own legacy of the heavens back in the islands where I’m from? How easy to sound as if that spot on earth where one might be instantly implanted were the most wondrous sight. More amazing is the realization that each spot is but a window to a land and sky or seascape configured by geological shifts and human history—the Philippine archipelago would draw gushes of awe from foreign visitors as much as a Filipino would of theirs like Vermont for me.

And so, as a traveler must zero in on destination, my friend and I drove for meal and bed in a century-old inn, which turned out as if we were unleashed into another time, again, one that I’ve merely conjured from art, books and the movies—the end of the 19th century preserved in Wilmington and lived by its people to the present day as effortlessly as waking up in both the dawns of their ancestors and their own. In the course of the trip, I discovered more of it, as the state of Vermont has simply resisted the physical corrosion of time. Apparently, families have carried on their legacies smoothly without seams.

My friend and I woke on our first day not just to a present of black-framed French windows thrown open to the mist seeping up rivers and streams that trickle around roots of flowering hydrangeas, the delicate picket fences of white balconied homes, farm estates rising on grassy knolls or glinting like an accent on foot hills but also a way of life as tactile as a child’s first touch of a goat’s horn or sinking fingertips into a sheep’s coat, a moment as vibrant as the moo of cows in the glen. A few solid pillars of silos pivot on one’s eyes, and sugar shacks divert one’s glimpse off the sprawl.

During a brief pause after a breakfast of squash omelet, made of fresh picked vegetables and multi-grain pancakes doused in farm made maple syrup, we rocked on a wooden swing at the balcony of our century-old inn, taking in the breeze that brushed an unhurried town of laced windows and a clock tower with a rooster pointing its beak where the wind goes. Strolling on Main Street in a pace that would have asked of dirndl skirts and a parasol, I couldn’t resist climbing a boardwalk that led to artists’ workshops, where in one, if it were not Labor Day, I could have sat for a pencil portrait.

An inner court shaded by cherry and apple trees, curves by the country store where the touch of woolen yarn from the local sheep triggered a picture I loved in my nursery book of a grandmother knitting on a rocking chair that was displayed, too, in a corner. We would later find in farmers’ markets fruit preserves in mason jars and maple sugar in clay pots alongside apples named after their grower like Robert Frost’s, yes, the poet we revered in our youth once lived in a cottage we did go to in nearby Shaftsbury, where he ventured, though failed, into farming.

Would this be a mere feast of travel memories? As a visitor, it’s a thought that is quite valid. But this is where my consciousness tore in half—I began to live them even taking some as my own legacy while knowing it’s but borrowed for a few days. Still, I realize, writing about it just now as stolen legacies from Wilmington locals, which by simply and staunchly preserving by living them have, unknowingly perhaps, enhanced their value by passing these on not to only to their children but to strangers who now claim a share like I have.

Published in Peregrine Notes by Alegria Imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, October 7, 2013

Filed under: opinion, personal essay, travel | Tags: alegria imperial, basilica, Business Mirror Philippines, Castel Sant'Angelo, Filipino, Greco-Roman civilization, Michelangelo, Musei Vaticani, Pope Francesco, Prati B&B, Rome, Sistine Chapel, St John Paul, St Peter, University of Santo Tomas, Vatican, Via Giulio Cesare

‘DI ba ang Vatican eh ’yung Basilica lang? Saan kayo tumira?” My sister asked on Facetime, catching me still awake from jet lag. “True, Citta del Vaticano, with its 800 inhabitants all working for the Holy See, has no place for pilgrims,” I replied, and stuttered through details that would take me days to smoothen.

Eleanor and I landed in Eternal Rome, so like a dream that at the Prati B&B of Alessandra Bounaccorsi on Via degli Scipioni, the grinding of a dumpster bolted us out of bed. Later walking toward Citta del Vaticano nine minutes away, we had seemed afloat on streets perfumed by wisteria streaming from balconies like in a movie, through fashion boutiques, trattoria and garden shops. And suddenly, in a mercato, bunches of musot (bulaklak ng kalabasa), apparently used with mozzarella in a panini, transported me to my grandmother’s table.

With driving à la Manila, we had dodged zooming cars as we crossed wide boulevards and, soon, waving off hustlers who offer “no lineup for a fee” to Vatican Square, spotting in us a kababayan they could perhaps inveigle. More of the unexpected in our Roman dream began; shortly, we bumped into a huddle of nuns. “Filipino?” asked one, and all three lit up as we nodded, “Oo!!” But “pilgrims all aren’t we?” chirped the youngest. They belong to a convent of the Sacred Heart Order in Sicily.

Rome’s goldish sun ushered us finally into Vatican Square by then packed with hundreds of herded tourists and pilgrims. So awed with our necks craned to heights scaled to eternity as in those childhood estampitas, we fell into a hush. We had to whirl around to take it all in, the basilica with its balcony from where the Pope emerges at Christmas and Easter on television to greet us in his urbi et orbi, its dome and the colonnade, the marble figures of Christ, the apostles and saints we know by heart poised in the wind—where we stood, a Roman necropolis in Nero’s time, early Christians had been executed by him, Saint Peter among those crucified.

Inside the basilica, overwhelmed by the magnificence but especially a touching-distance to the Cathedra Petri, Saint Peter’s papal chair, behind the baldachin, I resisted blinking. “Filipino? Yes, a Holy Mass will begin in a few minutes,” the usher let us into a girded area facing the high altar, pulling us away from the thick flow of just-gawking crowds. “Dominus vobiscum” reverberated through the sung Mass concelebrated by about a dozen cardinals; Eleanor and I responded from memory, “Et cum espiritu tuo,” even singing, “Pater Noster” and “Agnus Dei,” transported to the dawn Masses in the dark brick churches of our youth.

Brought back to the square by a gushing stream after Holy Mass, we plunged unknowingly into an expectant wave, crying out for “Papa Francesco!” Soon, from a window high above the colonnade, he addressed us, straining body-to-body to catch him, thumb-size from the ground, but suffused with his discernible smile, his warmth, reliving in me how I felt on first seeing Pope John Paul II, long ago it seems, as his open carriage wheeled through Magsaysay Boulevard in Manila.

A daunting line to Musei Vaticani almost crumbled our resolve next day. But we persevered from a tail that snaked uphill along the wall behind the basilica to papal palaces once, now museums of relics from Greco-Roman civilizations, through halls of ecclesiastical and classical art—the utmost being Michelangelo’s stunning ceiling paintings of the Sistine Chapel so configured as the tour’s climax. Amid such magnitude, suddenly I understood what perfection in art means decades after Humanities courses at the University of Santo Tomas—why shouldn’t Art be the Church’s legacy?

Still a palpable sense of vulnerability, yet impregnability pervade not only in the museums’ telling of Church history but also in preserved structures, as in the massive Castel Sant’Angelo, first a mausoleum of pope-kings then a fort, that till now looms over the Tiber just outside Vatican walls. Saint Michael the Archangel’s fierce vigilance from a tower still pierces peering eyes—he, whom Catholics invoke as shield from ruinous enemies and who Josie Darang calls when fear overtakes her, like in a cab hurtling through Manila’s streets.

“Filipino kayo, Ate?” A salesgirl had caught us in a shop outside the walls, browsing for souvenirs that could extend our precious euros. She filled a basket with refrigerator magnets, and spangled her breast with nylon scarves for us to choose; the whole stretch had a Filipino vying to pull in a fellow Filipino, reminding me of Central Market’s turo-turo aisles—a poignant note to an uplifting day.

After two days of pasta, Eleanor and I began to crave rice served only in a Pakistani restaurant as per tourist guides. But sauntering along Via Giulio Cesare, we had brushed by a hole-in-the-wall named Sarap. “Filipino kayo?” we asked the obvious; not only did we get a serving of rice but the all-male restaurant of young Pinoys also paired it with sarciadong salmon. The answer to my sister’s question by then had taken a twist: Indeed, by just being Filipinos, we found unexpected parts of us at every turn in Citta del Vaticano and Rome outside of its walls.

Published in Peregrine Notes, Alegria Imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, April 19, 2014

Filed under: opinion | Tags: "Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing", alegria imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, Canada, carved cherubim, crystal plates, Cultural Center of the Philippines, depression tinted glass, FedEx package, Felix Imperial II, greeting cards, immigrate, Intramuros, Lucio D. San Pedro, Lucrecia 'King' Kasilag, Miss Saigon, Natinal Artist, National Library, peregrine notes, UST's Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, wedding gifts

Unlike most others who immigrate and could leave home—which in truth, holds more emotions than someone we love—with a kin or caretaker, hence, to which seamlessly they could go back, my sister and I having been orphaned with me, childless and widowed, there was no one. Like a wild wind, we packed away our life, uprooting ourselves with waivers as heirs to leftover generations-owned farmlands, and handed over frayed documents of family history to relatives, whom we knew would know how to preserve them.

No hint at all in our growing up and adulthood that we would jam in two suitcases and in my case, a box I sent to my own self via UPS to Canada. Indeed, who has seen one’s future exactly the way it unravels especially those sudden turns? And who is ever prepared? For me, who my sister sponsored, it happened in less than three years. The arrival on a FedEx package from the Canadian embassy of my immigrant visa had felt like a storm and it churned on until my flight in two months.

In those months, remnants of years most of which I’ve forgotten or never knew had slumbered in corners, turned up. I tossed out from my mother’s beribboned cache, yellowed and crumbly report cards from the grades and up of my sister’s and mine, receipts and tax returns, notes from friends of my parents and ours, greeting cards and wedding invitations, my father’s heavily stained favorite hard plastic coffee cup that I must have snitched from Korean Airlines, and a steak plate he must have used a few times, among mounds and mounds of settled dust.

But I kept my parent’s love letters and my mother’s birth certificate and packed our photo albums especially a picture of my grandfather, a studio portrait of my father as a young man, my mother in the buff at eleven months and posed atop a wall in Intramuros during her years at the then, Philippine Normal School.

If I could, I wanted to keep more but wondered how and for whom in Canada? Like my late husband’s (Felix Imperial II), notes on restoration of Intramuros that I had hoped could be useful someday. After nights of poring through them, into boxes I loaded and delivered these to UST’s Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, and my own collections, along with researches I had hoped to write about to the National Library. I had asked Jack, a nephew, to take for a living museum he had mentioned he would build, my mother in-law’s wedding gifts of depression tinted glass sets, and brocaded crystal plates, as well as her hand-painted Japanese tea sets. So what else were in my suitcases and the UPS box?

It turns out that I packed randomly, taking along mostly souvenirs. Take this wood carved cherubim I had set on an accent table. The Northern Canadian sun now starkly reveals smudges on its varnished cheeks and tiny cracks behind its ear, and none of the smoky calm it had effused when I needed it in what seemed then, a life, which would just flow on.

The size of my palm, the late National Artist Lucrecia ‘King’ T. Kasilag sent it to me after an article I wrote of her came out in the defunct Chronicle. “You brought tears where sadness had long withered away. Only angels do that. Thank you,” she scrawled on a piece of yellowed wax paper she had used as a pillow to lay the angel.

A Union Jack lapel pin, too, had stayed in my jewelry box, with an unsigned note possibly in a rush with this scribbled message, “…from the ‘unlikely chorus guy for ‘Miss Saigon.’ Yet, you believed in me,” quoting from an article I wrote for the musical published in Philippine Star. At the CCP auditions in 1989, he stood out with his self-consciousness, being a first-timer then to Manila, flown-in on a sponsored ticket—his first airplane flight—from Tacloban. He had left this souvenir on my desk when he came back among those who ended their first contract to perform in London.

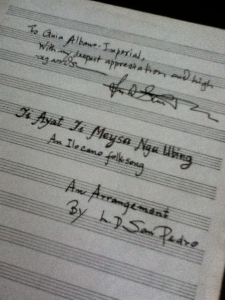

Even in Canada’s morning mist, this treasure stands out—an arrangement of “Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing” for voice and piano, that the late composer and conductor, Lucio D. San Pedro signed as a gift when he learned I’m Ilocano. From many lunches at the then, CCP buffet-eria to which he had treated me with pritong isda and guinisang monggo, finished off with turon, I had written about his music’s emotional content when he was declared National Artist that seemed to deeply link us.

None of the flimsy clothes I had worn for milestone events, like my book launching, fit neither spring’s wetness nor summer’s cool. Or could a pair of Marikina shoes last through undulating walks in the winter’s extreme cold and summer’s humidity. Like a birch, I now wear a new skin. Yet intact within me, at most times even simultaneously as evidenced by these souvenirs, is one still prowling Manila’s sunsets and the other, scouring Vancouver’s snow-covered peaks, as in permanent bilocation, perhaps?

Peregrine Notes at Business Mirror Opinion Page 08 June 2013

Filed under: opinion, personal essay | Tags: "Mythogyny", Business Mirror Philippines, Canada, citizenship, Cultural Center of the Philippines, election, Felix N. Imperial II, Girl Scouts of the Philippines, government media, grade school, high school, history, Intramuros, Josefa Llanes Escoda, Mayon, people's revolution, peregrine notes, Second Quarter Storm, The Flame, UST Museum of History, Vancouver, Women Elders in Action (WE*ACT

Citizenship if acquired by birth is simply a way of life, I believe, and not thought about. In truth, I never knew what it was being a Filipino citizen.

Was it in being solemn during the flag raising ceremonies from grade to high school? I recall how the class sergeant-at-arms used to get me back in the line because when bored I’d break out of it to talk with a seatmate, three warm bodies up. Was it joining the Girl Scouts of the Philippines? My troop learned how to cook bean soup in the beach though it was gritty, and yes, we planted a tree on Josefa Llanes Escoda Day behind the library in our high school, with none of us touching the soil, as we formed a lunette to watch our adviser and the principal, dig and put in a mango seedling that really never grew in the two years before my batch graduated.

Was it immersing myself in Philippine history not from learning in the classroom but stories I

gathered and later lived? My first encounter with colonial history left me tongue-tied from awe in an interview I had with the late Fr. Jesus Merino, OP, then director of UST’s museum of history and sciences for our college campus paper, The Flame.

If a moment in time had some kind of spirit, that interview must have cast a spell on me, so much so that I married a restoration architect, the late Felix N. Imperial II, who lived and breathed not only the ruins of Intramuros but the history and mythic stories embedded in them. One historical perception he inculcated in me is this: with thicker defense lines landward than seaward, the Spaniards definitely feared not invaders but Filipinos.

Did hopping in on those jeepneys that rounded us up, voters, in the three elections I got to vote make me a citizen? What a fiesta those days were with the candidates’ minions scrambling for a handshake or a hand as if to lead one to a seat of honor. I remember the grand fun an aunt, my age, and I had those election weeks in our childhood where our mothers, both public school teachers served as inspectors in the polling places, and we had stay in at our house, sharing a mat, pillows and a “mosquitero”as well as gothic stories told to us by our “kadkadua” (helper). By the time I had to vote, there was but one choice, Marcos, of my home province.

Was getting drawn into the maelstrom of the Second Quarter Storm, but not deeply knowing what I personally struggled to oppose, being a citizen? A former classmate whom I met in the shadows under which we would talk sent me away, doubting if I had to follow to the end our idols then, Voltaire Garcia, Joel Rocamora and Edgar Jopson. He told me that I, like a flotsam, simply lolled in the current because I felt none of the oppression fought against. I dropped out.

Years later, in my job for government media, I would meet in the flesh the haunting gauntness of hunger and suffering among malnourished children, farmers barely surviving their confusion that came with agrarian reform, wives scraping the soil during draught or railing at Mayon during an eruption one day before a harvest, and they wrenched my guts. But the same job had also brought me to paradise-like spots where I often wish to this day to be transported.

Yet, was I being a citizen when during the People’s Revolution what mattered most for me had to do with a deadline? And as if there had been no two raging rivers when later I leaped on to serve the new administration of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Digging into the arts like a ballet on Noli Me Tangere’s Elias, crying over a 100-year old pain, I must have finally synthesized my being a Filipino.

But again, I encouraged my sister, a chemist, to apply for immigration to Canada, convincing her of the moribund state of sciences in the Philippines. She kicked and screamed against leaving but her papers came faster than her prayers to be denied. Even faster was the approval of her petition to get me, and my papers to immigrate. I left behind a swath of life-artifacts from clearing out in three months a life I thought I’d never look back to again.

At the book launching of “Mythogyny” with Ted Alcuitas, then editor and publisher of now-defunct Silangan, where I served as associate editor

Had I shed off my being a Filipino when I bought a one-way ticket to Vancouver, and on landing signed my papers for permanent residency? That marked day one of my rights among them, health care and public services and the freedoms of assembly and speech as well as my responsibilities to uphold the same rights in others. Today the 22nd of July, a year ago, I took my oath of citizenship.

Did I turn Canadian in an instant? Yes and no. What I have become is more Filipino than I had imagined, possibly enhanced by my newly acquired freedom to find in Canada the threads I thought I had snapped broken when I left. I had unabashedly interwoven whom I am with these, often loudly qualifying my Filipino-ness from where I speak. And many times I would be told, ‘Ain’t that something!’

With members of Marpole Place, a community center run by the Marpole Oakdridge Area Council Society where I served a two-year elected secretary of the board

Peregrine Notes, Opinion Page, Business Mirror Philippines, July 22, 2012

Filed under: architecture, history, opinion, personal essay | Tags: alegria imperial, Ayuntamiento, Bacarra, Business Mirror Philippines, camino real, Colbourne House, colonical, Felix N. Imperial II, Intrramuros, living museum, Madrid, medieval walled city, monuments, Parian, political will, Puerta Santa ucia, San Agustin Church, structures, suildings, Vancouver

Built or erected in marble or stone, though some cast in metal, as landmarks in a country’s history or reminders of heroic deeds, monuments are so aimed at permanence or impregnability that for it to crumble one day hardly sound possible.

From what I learned from a restoration architect, my late husband Felix N. Imperial II, who studied the art at Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, and came home with quixotic dreams to apply what he had learned in Intramuros, keeping monuments intact requires more than stone masons, brick layers and other such hands (because it is as much a handiwork as building them), it asks of governments a political will—monuments belong to a nation, after all.

Indeed, a great number of such buildings or structures have defied decay from both centuries of natural and manmade disasters like tropical weather and wars such as San Agustin Church but especially elsewhere, those well-kept palaces and temples we often dream of walking into, if only to experience a moment of greatness or a glorious past that for many of us exists only in ether. Virtually a young city of 140 years, I see no such buildings here in Vancouver the likes of Philippine colonial structures most of them sadly left for time to eat away.

But why must a country like the Philippines struggling to stave poverty feed its past of non-living things? Answers to this all too common question with what seems obvious can drag into either despair or acrimony those who belong to the many sides of upholding or not patrimony. Such complex imbalance of forces to Felix had first, scaled down then later, hazed his dream: Intramuros would have given the Philippines a niche with the only medieval walled city in Asia among nations who showcase an inimitable past.

Except for the four gates, major parts of the walls, and the esplanade at Parian, a few of which he restored from the ground like Puerta Santa Lucia, most of his dream—if but one of the palaces, the Ayuntamiento, would have risen again—like moth wings slowly powdered and blown away. He died though, realizing how tiny a vessel man’s body to bear his dreams.

I think Felix was luckier in that he found closure and acceptance, in contrast to my paternal great grandfather who had built not a national monument but a personal one, which I suppose most families would recognize, “for his heirs”. Of these, there are several in Vancouver, most of them exquisitely cared for as living museums—one of them, the Colbourne House still breathing right across our gate.

My great grandfather’s house was of brick and mortar townsfolk of Bacarra called, kabite; its frame had been all I grew up with, a hulking shadow right across from our then fragile wood and bamboo house; apparently its interior was burnt. While almost a myth to Santiago, a nephew my age, and me, as adults we dwelt on snippets of what sounded like tall tales about it. Such as: a short bridge spanning a narrow moat, circling the house, washing the base of a fat rectangle of what we heard were stables, and dark wooden doors and windows that would open at midmorning to the camino real.

As Santiago and I sometimes sat on ruined steps of what we thought must be a grand staircase, we imagined a giant chandelier flooding a hall. Long dining tables like those stacked up under the creaky house we lived in must have been set on those monogrammed linens I once found in my grandmother’s trunk. Guests must have taken their liqueur from those Depression shot glasses, which we thought were toys in the buffet shelf of Santiago’s mom.

He and I hardly met during our university years in Manila. Not even when a court case stirred enmity in our families in a fight over yet another property, the land where our house stood—we had since lost the one where the kabite stood through another heir. Two decades later, poring over a heritage book about our town, we closed the pages miffed at nary a word about it.

During a rare visit to town after yet another decade, I missed seeing the landmark. As I later retraced my way with an aunt, I learned why: it was gone. Where it had loomed solid as a small mountain, there sprawled a thick growth of poison berries and cactuses. “Why, didn’t you know,” my aunt had said. “It crumbled like a heap of sand in the last earthquake.”

I would have to tell Santiago about it, I had vowed. But I decided to keep to myself a realization that no matter how massive some structures are like what my great grandfather built to defy impermanence, these could vanish. On the other hand, Felix’s view of Intramuros may yet be fulfilled: “it had lived through three centuries without me it would stay for others to dream of more.”

In photo: Puerta Santa Lucia facing the bay was totally ruined in WWII when a tank rammed into it; it was restored from the ground up by restoration architect Felix N. Imperial II, using traditional techniques of merely fitting the stones and without any reinforcing bars. He restored all four gates of the Walls.

Peregrine Notes, August 26, 2012, Business Mirror Philippines Opinion Page

Filed under: history, opinion, personal essay, travel | Tags: alegria imperial, Beethoven concertos, Business Mirror Philippines, buskers, Harrison Plaza, Imelda Marcos, jeepneys, Malate, Manhattan, Manila, Nick Joaquin, Paco Cemetery, peregrine notes, Roxas Blvd., Vancouver, West End

A city is

not a

landscape I now realize; it is a heart’s structure recalled blindly within its chambers. But it has taken time for me to sense that I prowl Vancouver’s streets in search of Manila, ‘city of my affections’, an endearment borrowed from my idol, Nick Joaquin.

Disbelief over this thought would strike anyone who has lived in it. Indeed, what do I miss in Manila? How could I not remember chaos in its streets, the high decibels of groaning engines, grating brakes of buses and jeepneys, music from stores and snack nooks vying for ears from across each other in streets? What about the grime, the rawness that has become its nature? Could these be what have heightened my senses?

In contrast, Vancouver is calm, rarely frazzled. Even during rush hours, only staccato steps, light laughter and snatches of conversation counter the deep breathing of pneumatic brakes plying their routes on main streets—no honking except when extreme danger of an accident pops up; only an ambulance and fire truck tandem is allowed to rent the air.

Buskers, as street performers with permits are called here, sometimes crochet music in the breeze. I once stood with a small crowd, letting pass a few buses I had walked on a stop to board, for a concert violinist stage an engaging performance of a few Beethoven concertos. With all my senses Manila has sharpened, none such moment passes without me plunging in it.

And because buses run on electric and no diesel in gas pumps, skies always tend to be iridescent except on foggy days in the fall and hazy ones in the spring, and especially when frozen in the winter. Perhaps it is under such clarity that has made Vancouverites commit to a clean city. I can’t say how it is achieved because I hardly catch cleaning dirt monsters with circular brushes in between wheels creeping through streets as in those mornings I did in Manhattan, and from a deep mist, Imelda’s orange clad sweeping brigade.

Once in a while when on my way to a meeting, I’d have to skirt around from getting sprayed by a power hose, dislodging dirt on the just-poured-with-disinfectant sidewalk. I had met waste pickers, too, donned in neon-striped, yes, orange vests, combing the streets and picking up bits sweepers missed. Discreet CCTV cameras notwithstanding, I’ve learned as a Vancouverite to keep my garbage or toss it away where I must.

And yet when drawn within to write, what creeps in are more of what I don’t see like Manila’s mangy dogs prowling and sniffing at the air like ghosts under a day moon or starved cats meowing their hunger at shadows. But more heart rending, who wouldn’t agree, are children on Roxas Blvd. who dart by your car window, a sniffling runny-nosed baby strapped to their fragile bodies, joints protruding, right hand up with eyes begging for sympathy or alms—and you later find out, the baby is no kin and whatever is given goes to whoever hired them.

Vancouver, too, has a few dark spots like a stretch of Hastings St. by Chinatown. Once in a while, I’d stumble on a homeless man in a corner. A couple of them have taken a permanent post by the granite steps of the cathedral. I had talked to youngish woman I caught sniffling as she counted the coins thrown into a hanky she knotted in the corners as in a box, learning of an abusive husband she just left but tearing her heart out was a daughter too, she hoped to go back for once she recovered from the horror of that day. Didn’t I listen to a similar story of a woman who cradled the asthmatic child she fanned as it labored to breath through an uneasy slumber by the entrance of Harrison Plaza? Could poverty of hearts possibly incarnated into ghosts possibly haunting me, I had wondered then.

Ahhh..but there’s Manila Bay that overpowers with its irony of vastness, fullness even grandeur at its incomparable blaze at sunset. And for true-blue Manilenos, the romance of pocket corners in stonewalls and intimate streets scented by champaca, veiled in shivering shadows of ilang-ilang trees like those in Malate. I merely close my eyes to find my late husband sketching on his favorite dappled stone bench at Paco Cemetery, as he waited for me to finish up at the then Inquirer offices.

Like carrying a hidden side of the day moon, I stroll on Vancouver’s West End relishing shades of giant chestnut leaves, often pausing in a pergola by a formal English garden once a private estate, then promptly getting on to the end of the street on English Bay. Most times silky smooth unlike swollen Manila Bay, this bay unfurls at the feet as if cajoling in tiny wave rolls. Even its late summer sunsets are sweet peach orange, bouncing against slopes of mountains framing it as if it were a stage for dreams. Now, do I sound like I’m switching my affections? I think I’m two-timing!

Published at Business Mirror Philippines in my weekly column,

“Peregrine Notes”, August 5, 2012