Filed under: opinion | Tags: "Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing", alegria imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, Canada, carved cherubim, crystal plates, Cultural Center of the Philippines, depression tinted glass, FedEx package, Felix Imperial II, greeting cards, immigrate, Intramuros, Lucio D. San Pedro, Lucrecia 'King' Kasilag, Miss Saigon, Natinal Artist, National Library, peregrine notes, UST's Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, wedding gifts

Unlike most others who immigrate and could leave home—which in truth, holds more emotions than someone we love—with a kin or caretaker, hence, to which seamlessly they could go back, my sister and I having been orphaned with me, childless and widowed, there was no one. Like a wild wind, we packed away our life, uprooting ourselves with waivers as heirs to leftover generations-owned farmlands, and handed over frayed documents of family history to relatives, whom we knew would know how to preserve them.

No hint at all in our growing up and adulthood that we would jam in two suitcases and in my case, a box I sent to my own self via UPS to Canada. Indeed, who has seen one’s future exactly the way it unravels especially those sudden turns? And who is ever prepared? For me, who my sister sponsored, it happened in less than three years. The arrival on a FedEx package from the Canadian embassy of my immigrant visa had felt like a storm and it churned on until my flight in two months.

In those months, remnants of years most of which I’ve forgotten or never knew had slumbered in corners, turned up. I tossed out from my mother’s beribboned cache, yellowed and crumbly report cards from the grades and up of my sister’s and mine, receipts and tax returns, notes from friends of my parents and ours, greeting cards and wedding invitations, my father’s heavily stained favorite hard plastic coffee cup that I must have snitched from Korean Airlines, and a steak plate he must have used a few times, among mounds and mounds of settled dust.

But I kept my parent’s love letters and my mother’s birth certificate and packed our photo albums especially a picture of my grandfather, a studio portrait of my father as a young man, my mother in the buff at eleven months and posed atop a wall in Intramuros during her years at the then, Philippine Normal School.

If I could, I wanted to keep more but wondered how and for whom in Canada? Like my late husband’s (Felix Imperial II), notes on restoration of Intramuros that I had hoped could be useful someday. After nights of poring through them, into boxes I loaded and delivered these to UST’s Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, and my own collections, along with researches I had hoped to write about to the National Library. I had asked Jack, a nephew, to take for a living museum he had mentioned he would build, my mother in-law’s wedding gifts of depression tinted glass sets, and brocaded crystal plates, as well as her hand-painted Japanese tea sets. So what else were in my suitcases and the UPS box?

It turns out that I packed randomly, taking along mostly souvenirs. Take this wood carved cherubim I had set on an accent table. The Northern Canadian sun now starkly reveals smudges on its varnished cheeks and tiny cracks behind its ear, and none of the smoky calm it had effused when I needed it in what seemed then, a life, which would just flow on.

The size of my palm, the late National Artist Lucrecia ‘King’ T. Kasilag sent it to me after an article I wrote of her came out in the defunct Chronicle. “You brought tears where sadness had long withered away. Only angels do that. Thank you,” she scrawled on a piece of yellowed wax paper she had used as a pillow to lay the angel.

A Union Jack lapel pin, too, had stayed in my jewelry box, with an unsigned note possibly in a rush with this scribbled message, “…from the ‘unlikely chorus guy for ‘Miss Saigon.’ Yet, you believed in me,” quoting from an article I wrote for the musical published in Philippine Star. At the CCP auditions in 1989, he stood out with his self-consciousness, being a first-timer then to Manila, flown-in on a sponsored ticket—his first airplane flight—from Tacloban. He had left this souvenir on my desk when he came back among those who ended their first contract to perform in London.

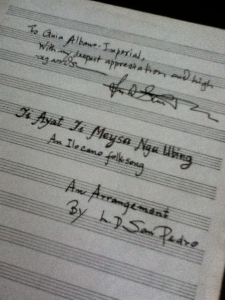

Even in Canada’s morning mist, this treasure stands out—an arrangement of “Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing” for voice and piano, that the late composer and conductor, Lucio D. San Pedro signed as a gift when he learned I’m Ilocano. From many lunches at the then, CCP buffet-eria to which he had treated me with pritong isda and guinisang monggo, finished off with turon, I had written about his music’s emotional content when he was declared National Artist that seemed to deeply link us.

None of the flimsy clothes I had worn for milestone events, like my book launching, fit neither spring’s wetness nor summer’s cool. Or could a pair of Marikina shoes last through undulating walks in the winter’s extreme cold and summer’s humidity. Like a birch, I now wear a new skin. Yet intact within me, at most times even simultaneously as evidenced by these souvenirs, is one still prowling Manila’s sunsets and the other, scouring Vancouver’s snow-covered peaks, as in permanent bilocation, perhaps?

Peregrine Notes at Business Mirror Opinion Page 08 June 2013

Filed under: opinion, personal essay | Tags: "Mythogyny", Business Mirror Philippines, Canada, citizenship, Cultural Center of the Philippines, election, Felix N. Imperial II, Girl Scouts of the Philippines, government media, grade school, high school, history, Intramuros, Josefa Llanes Escoda, Mayon, people's revolution, peregrine notes, Second Quarter Storm, The Flame, UST Museum of History, Vancouver, Women Elders in Action (WE*ACT

Citizenship if acquired by birth is simply a way of life, I believe, and not thought about. In truth, I never knew what it was being a Filipino citizen.

Was it in being solemn during the flag raising ceremonies from grade to high school? I recall how the class sergeant-at-arms used to get me back in the line because when bored I’d break out of it to talk with a seatmate, three warm bodies up. Was it joining the Girl Scouts of the Philippines? My troop learned how to cook bean soup in the beach though it was gritty, and yes, we planted a tree on Josefa Llanes Escoda Day behind the library in our high school, with none of us touching the soil, as we formed a lunette to watch our adviser and the principal, dig and put in a mango seedling that really never grew in the two years before my batch graduated.

Was it immersing myself in Philippine history not from learning in the classroom but stories I

gathered and later lived? My first encounter with colonial history left me tongue-tied from awe in an interview I had with the late Fr. Jesus Merino, OP, then director of UST’s museum of history and sciences for our college campus paper, The Flame.

If a moment in time had some kind of spirit, that interview must have cast a spell on me, so much so that I married a restoration architect, the late Felix N. Imperial II, who lived and breathed not only the ruins of Intramuros but the history and mythic stories embedded in them. One historical perception he inculcated in me is this: with thicker defense lines landward than seaward, the Spaniards definitely feared not invaders but Filipinos.

Did hopping in on those jeepneys that rounded us up, voters, in the three elections I got to vote make me a citizen? What a fiesta those days were with the candidates’ minions scrambling for a handshake or a hand as if to lead one to a seat of honor. I remember the grand fun an aunt, my age, and I had those election weeks in our childhood where our mothers, both public school teachers served as inspectors in the polling places, and we had stay in at our house, sharing a mat, pillows and a “mosquitero”as well as gothic stories told to us by our “kadkadua” (helper). By the time I had to vote, there was but one choice, Marcos, of my home province.

Was getting drawn into the maelstrom of the Second Quarter Storm, but not deeply knowing what I personally struggled to oppose, being a citizen? A former classmate whom I met in the shadows under which we would talk sent me away, doubting if I had to follow to the end our idols then, Voltaire Garcia, Joel Rocamora and Edgar Jopson. He told me that I, like a flotsam, simply lolled in the current because I felt none of the oppression fought against. I dropped out.

Years later, in my job for government media, I would meet in the flesh the haunting gauntness of hunger and suffering among malnourished children, farmers barely surviving their confusion that came with agrarian reform, wives scraping the soil during draught or railing at Mayon during an eruption one day before a harvest, and they wrenched my guts. But the same job had also brought me to paradise-like spots where I often wish to this day to be transported.

Yet, was I being a citizen when during the People’s Revolution what mattered most for me had to do with a deadline? And as if there had been no two raging rivers when later I leaped on to serve the new administration of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Digging into the arts like a ballet on Noli Me Tangere’s Elias, crying over a 100-year old pain, I must have finally synthesized my being a Filipino.

But again, I encouraged my sister, a chemist, to apply for immigration to Canada, convincing her of the moribund state of sciences in the Philippines. She kicked and screamed against leaving but her papers came faster than her prayers to be denied. Even faster was the approval of her petition to get me, and my papers to immigrate. I left behind a swath of life-artifacts from clearing out in three months a life I thought I’d never look back to again.

At the book launching of “Mythogyny” with Ted Alcuitas, then editor and publisher of now-defunct Silangan, where I served as associate editor

Had I shed off my being a Filipino when I bought a one-way ticket to Vancouver, and on landing signed my papers for permanent residency? That marked day one of my rights among them, health care and public services and the freedoms of assembly and speech as well as my responsibilities to uphold the same rights in others. Today the 22nd of July, a year ago, I took my oath of citizenship.

Did I turn Canadian in an instant? Yes and no. What I have become is more Filipino than I had imagined, possibly enhanced by my newly acquired freedom to find in Canada the threads I thought I had snapped broken when I left. I had unabashedly interwoven whom I am with these, often loudly qualifying my Filipino-ness from where I speak. And many times I would be told, ‘Ain’t that something!’

With members of Marpole Place, a community center run by the Marpole Oakdridge Area Council Society where I served a two-year elected secretary of the board

Peregrine Notes, Opinion Page, Business Mirror Philippines, July 22, 2012

Filed under: essay, opinion, thoughts | Tags: alegria imperial, alien, ancestral lot, Baclaran, business mirror, Canada, Ceferino M. 'Nonoy' Acosta III, funeral, generations, home, homing birds, impermeable, invisible, Manila, Ninoy Aquino International Airport, Paz Memorial Homes, peregrine notes, refelction, relatives, Roxas Blvd., The Little Prince, tide surge, unchanged, United Airlines

The word makes me wonder if most of us, like me, were born to leave home and later pine to return. Are we somehow reflections of homing birds, like the swallows of Capistrano, or the terns and geese of North America? Or closer to what I know, do we return where we come from like the salmon of British Columbia that swims back when matured to the river where it was spawned?

But unlike birds and fishes, home, for me, is no longer a place. I suppose it has ceased being one as I changed from one whom I recall even as recently as a year ago. This sense of being alien, which in a way is a reality, could have started to deepen like a whorl in my heart since six years ago when I hurriedly unloaded six decades of my life to live in Canada. At first, I couldn’t imagine going back home.

Where is home? Not that last apartment I emptied not only of accumulated debris but also of mementos and tags of moments lived, which my mother moved from house to house. Or an architect’s house that stood in an ancestral lot owned by five generations I was married into, which I had to sell. Where my sister and I lived with our parents for twenty years close to her high school is now a meaningless shell along smoggy Ramon Magsaysay Boulevard.

Not even where I was born already a vacant space shaded by an ageing pomelo by the time I learned how to read, the borrowed hut lent by an uncle of my father for my mother’s family driven into homelessness by WWII. Or where I grew up with my father’s mother said to be another temporary home built after their stone house from across was burnt. When my mother had to move back to her mother’s for care on the birth of my sister and my other grandmother debilitated with arthritis had to be hauled to a daughter in Manila, I watched it painfully torn down piece by piece and hoisted on to a carabao cart, with my childhood in it.

Massive convent walls where I was sent after high school and the dormitory run by nuns from across UST where I lived for six years sort of healed the gnawing loss I nursed from seeing those fragile walls just gone but I couldn’t call them home. Where then lies home? In my recent homecoming to Manila, I realized that home is both not a place and a structure but something “visible only to the heart” as The Little Prince of Antoine de Saint Exupery told the fox.

My homecoming last month was both ideal and deeply sad. Like a tide surge, my cousin’s death, Ceferino ‘Nonoy’ M. Acosta III, left no space for me to waver about a flight and waffle about gifts to bring. I was so wrapped up in my emotions that the smog, which swarmed the path of United Airlines on its descent to NAIA, failed to daunt me. Nor did the snarl in Baclaran, being a Wednesday, through Roxas Blvd. unnerve me. The landscape though felt shrunken and tighter with buildings now unfamiliar to me, and a crowd thrice multiplied; yet as the SUV that fetched me coughed through clogged streets, it had seemed normal.

I couldn’t guess how I would feel arriving at Paz Memorial Homes; it would be my first as a balikbayan. But with my first step into the chapel where Nonoy lay in state, I felt like I’ve been in it the day before—how many times have I bristled in the arctic air conditioning during a wake of relatives and friends? My uncle and aunt soon swept me in their grieving arms and we wept, sobbing words for the smiling Nonoy, a scene I have watched with other relatives countless of times.

When I turned to the faces riveted on us, there were my other uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces, nephews, relatives, and former neighbors sniveling with us. While most like me bore marks of time’s subtle scratches, each was whom I knew through the eyes—that invisible space impermeable to time, where I met theirs and my unchanged self.

We laughed, relishing not what was said but simply from the thrill of retrieving lost moments of being together. In the few days that followed, as we exchanged more of such moments–some with Nonoy in our midst–we kept flinging open the closed doors that had been shut by years. And as the burial crowd thinned out, when our clan gathered for what for me was yet another last time together, I had ceased to wonder if I have a home to go back to.

So like a homing bird and the salmon I had managed, indeed, with a tracker so precise scientists remain baffled, to land in or swim back to the same exact spot called, home. Yet unlike them, it’s not a spot I arrived at but a roof with walls I carry around unseen.

Published on January 6, 2013 Peregrine Notes, Opinion Page, Business Mirror Philippines

Photo: waders roosting at high tide in Roebuck Bay, Australia courtesy of wikipedia