Filed under: opinion, personal essay, travel | Tags: alegria imperial, basilica, Business Mirror Philippines, Castel Sant'Angelo, Filipino, Greco-Roman civilization, Michelangelo, Musei Vaticani, Pope Francesco, Prati B&B, Rome, Sistine Chapel, St John Paul, St Peter, University of Santo Tomas, Vatican, Via Giulio Cesare

‘DI ba ang Vatican eh ’yung Basilica lang? Saan kayo tumira?” My sister asked on Facetime, catching me still awake from jet lag. “True, Citta del Vaticano, with its 800 inhabitants all working for the Holy See, has no place for pilgrims,” I replied, and stuttered through details that would take me days to smoothen.

Eleanor and I landed in Eternal Rome, so like a dream that at the Prati B&B of Alessandra Bounaccorsi on Via degli Scipioni, the grinding of a dumpster bolted us out of bed. Later walking toward Citta del Vaticano nine minutes away, we had seemed afloat on streets perfumed by wisteria streaming from balconies like in a movie, through fashion boutiques, trattoria and garden shops. And suddenly, in a mercato, bunches of musot (bulaklak ng kalabasa), apparently used with mozzarella in a panini, transported me to my grandmother’s table.

With driving à la Manila, we had dodged zooming cars as we crossed wide boulevards and, soon, waving off hustlers who offer “no lineup for a fee” to Vatican Square, spotting in us a kababayan they could perhaps inveigle. More of the unexpected in our Roman dream began; shortly, we bumped into a huddle of nuns. “Filipino?” asked one, and all three lit up as we nodded, “Oo!!” But “pilgrims all aren’t we?” chirped the youngest. They belong to a convent of the Sacred Heart Order in Sicily.

Rome’s goldish sun ushered us finally into Vatican Square by then packed with hundreds of herded tourists and pilgrims. So awed with our necks craned to heights scaled to eternity as in those childhood estampitas, we fell into a hush. We had to whirl around to take it all in, the basilica with its balcony from where the Pope emerges at Christmas and Easter on television to greet us in his urbi et orbi, its dome and the colonnade, the marble figures of Christ, the apostles and saints we know by heart poised in the wind—where we stood, a Roman necropolis in Nero’s time, early Christians had been executed by him, Saint Peter among those crucified.

Inside the basilica, overwhelmed by the magnificence but especially a touching-distance to the Cathedra Petri, Saint Peter’s papal chair, behind the baldachin, I resisted blinking. “Filipino? Yes, a Holy Mass will begin in a few minutes,” the usher let us into a girded area facing the high altar, pulling us away from the thick flow of just-gawking crowds. “Dominus vobiscum” reverberated through the sung Mass concelebrated by about a dozen cardinals; Eleanor and I responded from memory, “Et cum espiritu tuo,” even singing, “Pater Noster” and “Agnus Dei,” transported to the dawn Masses in the dark brick churches of our youth.

Brought back to the square by a gushing stream after Holy Mass, we plunged unknowingly into an expectant wave, crying out for “Papa Francesco!” Soon, from a window high above the colonnade, he addressed us, straining body-to-body to catch him, thumb-size from the ground, but suffused with his discernible smile, his warmth, reliving in me how I felt on first seeing Pope John Paul II, long ago it seems, as his open carriage wheeled through Magsaysay Boulevard in Manila.

A daunting line to Musei Vaticani almost crumbled our resolve next day. But we persevered from a tail that snaked uphill along the wall behind the basilica to papal palaces once, now museums of relics from Greco-Roman civilizations, through halls of ecclesiastical and classical art—the utmost being Michelangelo’s stunning ceiling paintings of the Sistine Chapel so configured as the tour’s climax. Amid such magnitude, suddenly I understood what perfection in art means decades after Humanities courses at the University of Santo Tomas—why shouldn’t Art be the Church’s legacy?

Still a palpable sense of vulnerability, yet impregnability pervade not only in the museums’ telling of Church history but also in preserved structures, as in the massive Castel Sant’Angelo, first a mausoleum of pope-kings then a fort, that till now looms over the Tiber just outside Vatican walls. Saint Michael the Archangel’s fierce vigilance from a tower still pierces peering eyes—he, whom Catholics invoke as shield from ruinous enemies and who Josie Darang calls when fear overtakes her, like in a cab hurtling through Manila’s streets.

“Filipino kayo, Ate?” A salesgirl had caught us in a shop outside the walls, browsing for souvenirs that could extend our precious euros. She filled a basket with refrigerator magnets, and spangled her breast with nylon scarves for us to choose; the whole stretch had a Filipino vying to pull in a fellow Filipino, reminding me of Central Market’s turo-turo aisles—a poignant note to an uplifting day.

After two days of pasta, Eleanor and I began to crave rice served only in a Pakistani restaurant as per tourist guides. But sauntering along Via Giulio Cesare, we had brushed by a hole-in-the-wall named Sarap. “Filipino kayo?” we asked the obvious; not only did we get a serving of rice but the all-male restaurant of young Pinoys also paired it with sarciadong salmon. The answer to my sister’s question by then had taken a twist: Indeed, by just being Filipinos, we found unexpected parts of us at every turn in Citta del Vaticano and Rome outside of its walls.

Published in Peregrine Notes, Alegria Imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, April 19, 2014

Filed under: opinion | Tags: alegria imperial, business mirror, education, father, peregrine notes, Philets, Philippine Graphic, poetry, Poetry Reading, public relations, The Prince and the Pauper, travel page, University of Santo Tomas, writing

Often, intensely quiet in insulated spaces is how days unfold here, undistracted spaces that let roam vibrant memories like this week. As I write this piece midway through selecting my poems for a Poetry Reading event at the Chapters Bookstore downtown, my first ever, sponsored by Vancouver Haiku Group to which I belong, the late Serafin Albano, my father—a central figure in my writing life—looms largely.

If he did not impose his will on my choice of what I’d be, I could be languishing now in a dark even dank office somewhere in a turn-of-the century old building in Avenida where notaries get signed and sealed for a small fee if I didn’t get a teaching job, that is. He lugged me instead led by the youngest of my mother’s brothers, then in his junior year at UST’s Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, to the office of the dean. I had waffled but in a quick turn of mind, I plunged into a future of writing. But I ended up neither a journalist nor a poet not until decades after graduation and long after he had died. Instead, I sneaked into a writing career via public relations, ghost-writing for years.

From a back glance this morning in a continent way across the Pacific, I feel that I had glossed over how my father felt through those years I got stalled in what he couldn’t understand as tossing out words and images in anonymity. Picking through hints, I remember how he must have had great dreams of my name spangled on printed pages, as in his first wrapped gift on my eighth birthday, Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper that he dedicated with a noble quote beyond a child’s grasp: “Education supplants intelligence but does not supply it.” Telling me a book was easier to find, he had hoped this gift would inspire me to write more—I had a year before then, sent him, where he lived and worked in Manila, a four-line poem scrawled on grade two paper, a ruse to ask for a doll.

Yes, I did write but not feeling particularly inspired only fed with words, perhaps, from books he and my mother piled on me. Early in college, I wrote a hilarious narrative on how giggly, overacting, mostly spoiled girls in a dormitory run by nuns from across UST, my first published article in Philippine Graphic magazine, in its ‘Student’s Page’ with my picture and a note on the author. It had so elated my father, he carried the issue opened on that page and showed it to everyone including waitresses. Some months later, I followed it up with an essay on fishes, which I used as a metaphor for the kinds of people we get to know in this “ocean of life”. I made him so happy he treated me out, and my friends at the dorm to dinner almost weekly. But none came long after that.

In a sudden spurt, probably stimulated by my travels in my job at the then National Media Production Center, I began weaving words into lyrical pieces for Dick Pascual’s travel page at the defunct Daily Express. My father brought each piece to Magallanes Drive, trudging his way through grime-textured air. Among the stash I dug out when clearing out stuff to immigrate to here, was a rough album he sewed on the side of those published pieces. And then again, I skidded into anonymity.

Still, we argued furiously about writing. Our last word-spars focused on my defunct Newsday lifestyle page, my first ever newspaper job. More critical and cutting than the late Teddy Berbano, then managing editor, my father devastated me by his correctness those evenings I dropped by to see him and my mother on my way to my own home—I had married by then. He had died by the time my page started shaping up and later when I wrote weekly full-page feature stories for Sunday lifestyle at Inquirer.

Once coming home from New York much later, I found the fiction writing paperback he kept sliding before me that I left unread, and cried and cried. The author, R. V. Cassill, also authored the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction from which my instructor in a writing course I took at NYU’s Continuing Education program selected our readings. Leafing through the pages he dog-eared and underlined, I had realized it’s exactly what I was learning. I’ve grappled with challenges he couldn’t have imagined like writing in NY alongside native speakers of English. But each step of the way, I would find his imprint.

Could a father shape a child’s destiny, carving a path like mine that I had long wavered to follow straight on? On the podium to read my published and award-winning poems here in Vancouver, a crowd their blond, blue, hazel, gray, maybe some black even green Irish eyes on me, I’m sure my father though invisible to all would be seated in the front row.

Published in Peregrine Notes by Alegria Imperial, Business Mirror, Manila, June 24, 2013

Filed under: opinion | Tags: "Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing", alegria imperial, Business Mirror Philippines, Canada, carved cherubim, crystal plates, Cultural Center of the Philippines, depression tinted glass, FedEx package, Felix Imperial II, greeting cards, immigrate, Intramuros, Lucio D. San Pedro, Lucrecia 'King' Kasilag, Miss Saigon, Natinal Artist, National Library, peregrine notes, UST's Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, wedding gifts

Unlike most others who immigrate and could leave home—which in truth, holds more emotions than someone we love—with a kin or caretaker, hence, to which seamlessly they could go back, my sister and I having been orphaned with me, childless and widowed, there was no one. Like a wild wind, we packed away our life, uprooting ourselves with waivers as heirs to leftover generations-owned farmlands, and handed over frayed documents of family history to relatives, whom we knew would know how to preserve them.

No hint at all in our growing up and adulthood that we would jam in two suitcases and in my case, a box I sent to my own self via UPS to Canada. Indeed, who has seen one’s future exactly the way it unravels especially those sudden turns? And who is ever prepared? For me, who my sister sponsored, it happened in less than three years. The arrival on a FedEx package from the Canadian embassy of my immigrant visa had felt like a storm and it churned on until my flight in two months.

In those months, remnants of years most of which I’ve forgotten or never knew had slumbered in corners, turned up. I tossed out from my mother’s beribboned cache, yellowed and crumbly report cards from the grades and up of my sister’s and mine, receipts and tax returns, notes from friends of my parents and ours, greeting cards and wedding invitations, my father’s heavily stained favorite hard plastic coffee cup that I must have snitched from Korean Airlines, and a steak plate he must have used a few times, among mounds and mounds of settled dust.

But I kept my parent’s love letters and my mother’s birth certificate and packed our photo albums especially a picture of my grandfather, a studio portrait of my father as a young man, my mother in the buff at eleven months and posed atop a wall in Intramuros during her years at the then, Philippine Normal School.

If I could, I wanted to keep more but wondered how and for whom in Canada? Like my late husband’s (Felix Imperial II), notes on restoration of Intramuros that I had hoped could be useful someday. After nights of poring through them, into boxes I loaded and delivered these to UST’s Center for Conservation of Cultural Property and Environment in the Tropics, and my own collections, along with researches I had hoped to write about to the National Library. I had asked Jack, a nephew, to take for a living museum he had mentioned he would build, my mother in-law’s wedding gifts of depression tinted glass sets, and brocaded crystal plates, as well as her hand-painted Japanese tea sets. So what else were in my suitcases and the UPS box?

It turns out that I packed randomly, taking along mostly souvenirs. Take this wood carved cherubim I had set on an accent table. The Northern Canadian sun now starkly reveals smudges on its varnished cheeks and tiny cracks behind its ear, and none of the smoky calm it had effused when I needed it in what seemed then, a life, which would just flow on.

The size of my palm, the late National Artist Lucrecia ‘King’ T. Kasilag sent it to me after an article I wrote of her came out in the defunct Chronicle. “You brought tears where sadness had long withered away. Only angels do that. Thank you,” she scrawled on a piece of yellowed wax paper she had used as a pillow to lay the angel.

A Union Jack lapel pin, too, had stayed in my jewelry box, with an unsigned note possibly in a rush with this scribbled message, “…from the ‘unlikely chorus guy for ‘Miss Saigon.’ Yet, you believed in me,” quoting from an article I wrote for the musical published in Philippine Star. At the CCP auditions in 1989, he stood out with his self-consciousness, being a first-timer then to Manila, flown-in on a sponsored ticket—his first airplane flight—from Tacloban. He had left this souvenir on my desk when he came back among those who ended their first contract to perform in London.

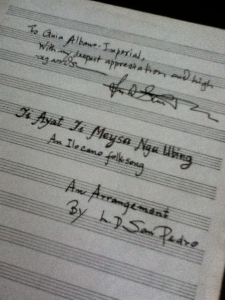

Even in Canada’s morning mist, this treasure stands out—an arrangement of “Ti Ayat ti Maysa nga Ubing” for voice and piano, that the late composer and conductor, Lucio D. San Pedro signed as a gift when he learned I’m Ilocano. From many lunches at the then, CCP buffet-eria to which he had treated me with pritong isda and guinisang monggo, finished off with turon, I had written about his music’s emotional content when he was declared National Artist that seemed to deeply link us.

None of the flimsy clothes I had worn for milestone events, like my book launching, fit neither spring’s wetness nor summer’s cool. Or could a pair of Marikina shoes last through undulating walks in the winter’s extreme cold and summer’s humidity. Like a birch, I now wear a new skin. Yet intact within me, at most times even simultaneously as evidenced by these souvenirs, is one still prowling Manila’s sunsets and the other, scouring Vancouver’s snow-covered peaks, as in permanent bilocation, perhaps?

Peregrine Notes at Business Mirror Opinion Page 08 June 2013

Filed under: architecture, history, opinion, personal essay | Tags: alegria imperial, Ayuntamiento, Bacarra, Business Mirror Philippines, camino real, Colbourne House, colonical, Felix N. Imperial II, Intrramuros, living museum, Madrid, medieval walled city, monuments, Parian, political will, Puerta Santa ucia, San Agustin Church, structures, suildings, Vancouver

Built or erected in marble or stone, though some cast in metal, as landmarks in a country’s history or reminders of heroic deeds, monuments are so aimed at permanence or impregnability that for it to crumble one day hardly sound possible.

From what I learned from a restoration architect, my late husband Felix N. Imperial II, who studied the art at Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, and came home with quixotic dreams to apply what he had learned in Intramuros, keeping monuments intact requires more than stone masons, brick layers and other such hands (because it is as much a handiwork as building them), it asks of governments a political will—monuments belong to a nation, after all.

Indeed, a great number of such buildings or structures have defied decay from both centuries of natural and manmade disasters like tropical weather and wars such as San Agustin Church but especially elsewhere, those well-kept palaces and temples we often dream of walking into, if only to experience a moment of greatness or a glorious past that for many of us exists only in ether. Virtually a young city of 140 years, I see no such buildings here in Vancouver the likes of Philippine colonial structures most of them sadly left for time to eat away.

But why must a country like the Philippines struggling to stave poverty feed its past of non-living things? Answers to this all too common question with what seems obvious can drag into either despair or acrimony those who belong to the many sides of upholding or not patrimony. Such complex imbalance of forces to Felix had first, scaled down then later, hazed his dream: Intramuros would have given the Philippines a niche with the only medieval walled city in Asia among nations who showcase an inimitable past.

Except for the four gates, major parts of the walls, and the esplanade at Parian, a few of which he restored from the ground like Puerta Santa Lucia, most of his dream—if but one of the palaces, the Ayuntamiento, would have risen again—like moth wings slowly powdered and blown away. He died though, realizing how tiny a vessel man’s body to bear his dreams.

I think Felix was luckier in that he found closure and acceptance, in contrast to my paternal great grandfather who had built not a national monument but a personal one, which I suppose most families would recognize, “for his heirs”. Of these, there are several in Vancouver, most of them exquisitely cared for as living museums—one of them, the Colbourne House still breathing right across our gate.

My great grandfather’s house was of brick and mortar townsfolk of Bacarra called, kabite; its frame had been all I grew up with, a hulking shadow right across from our then fragile wood and bamboo house; apparently its interior was burnt. While almost a myth to Santiago, a nephew my age, and me, as adults we dwelt on snippets of what sounded like tall tales about it. Such as: a short bridge spanning a narrow moat, circling the house, washing the base of a fat rectangle of what we heard were stables, and dark wooden doors and windows that would open at midmorning to the camino real.

As Santiago and I sometimes sat on ruined steps of what we thought must be a grand staircase, we imagined a giant chandelier flooding a hall. Long dining tables like those stacked up under the creaky house we lived in must have been set on those monogrammed linens I once found in my grandmother’s trunk. Guests must have taken their liqueur from those Depression shot glasses, which we thought were toys in the buffet shelf of Santiago’s mom.

He and I hardly met during our university years in Manila. Not even when a court case stirred enmity in our families in a fight over yet another property, the land where our house stood—we had since lost the one where the kabite stood through another heir. Two decades later, poring over a heritage book about our town, we closed the pages miffed at nary a word about it.

During a rare visit to town after yet another decade, I missed seeing the landmark. As I later retraced my way with an aunt, I learned why: it was gone. Where it had loomed solid as a small mountain, there sprawled a thick growth of poison berries and cactuses. “Why, didn’t you know,” my aunt had said. “It crumbled like a heap of sand in the last earthquake.”

I would have to tell Santiago about it, I had vowed. But I decided to keep to myself a realization that no matter how massive some structures are like what my great grandfather built to defy impermanence, these could vanish. On the other hand, Felix’s view of Intramuros may yet be fulfilled: “it had lived through three centuries without me it would stay for others to dream of more.”

In photo: Puerta Santa Lucia facing the bay was totally ruined in WWII when a tank rammed into it; it was restored from the ground up by restoration architect Felix N. Imperial II, using traditional techniques of merely fitting the stones and without any reinforcing bars. He restored all four gates of the Walls.

Peregrine Notes, August 26, 2012, Business Mirror Philippines Opinion Page

Filed under: history, opinion, personal essay, travel | Tags: alegria imperial, Beethoven concertos, Business Mirror Philippines, buskers, Harrison Plaza, Imelda Marcos, jeepneys, Malate, Manhattan, Manila, Nick Joaquin, Paco Cemetery, peregrine notes, Roxas Blvd., Vancouver, West End

A city is

not a

landscape I now realize; it is a heart’s structure recalled blindly within its chambers. But it has taken time for me to sense that I prowl Vancouver’s streets in search of Manila, ‘city of my affections’, an endearment borrowed from my idol, Nick Joaquin.

Disbelief over this thought would strike anyone who has lived in it. Indeed, what do I miss in Manila? How could I not remember chaos in its streets, the high decibels of groaning engines, grating brakes of buses and jeepneys, music from stores and snack nooks vying for ears from across each other in streets? What about the grime, the rawness that has become its nature? Could these be what have heightened my senses?

In contrast, Vancouver is calm, rarely frazzled. Even during rush hours, only staccato steps, light laughter and snatches of conversation counter the deep breathing of pneumatic brakes plying their routes on main streets—no honking except when extreme danger of an accident pops up; only an ambulance and fire truck tandem is allowed to rent the air.

Buskers, as street performers with permits are called here, sometimes crochet music in the breeze. I once stood with a small crowd, letting pass a few buses I had walked on a stop to board, for a concert violinist stage an engaging performance of a few Beethoven concertos. With all my senses Manila has sharpened, none such moment passes without me plunging in it.

And because buses run on electric and no diesel in gas pumps, skies always tend to be iridescent except on foggy days in the fall and hazy ones in the spring, and especially when frozen in the winter. Perhaps it is under such clarity that has made Vancouverites commit to a clean city. I can’t say how it is achieved because I hardly catch cleaning dirt monsters with circular brushes in between wheels creeping through streets as in those mornings I did in Manhattan, and from a deep mist, Imelda’s orange clad sweeping brigade.

Once in a while when on my way to a meeting, I’d have to skirt around from getting sprayed by a power hose, dislodging dirt on the just-poured-with-disinfectant sidewalk. I had met waste pickers, too, donned in neon-striped, yes, orange vests, combing the streets and picking up bits sweepers missed. Discreet CCTV cameras notwithstanding, I’ve learned as a Vancouverite to keep my garbage or toss it away where I must.

And yet when drawn within to write, what creeps in are more of what I don’t see like Manila’s mangy dogs prowling and sniffing at the air like ghosts under a day moon or starved cats meowing their hunger at shadows. But more heart rending, who wouldn’t agree, are children on Roxas Blvd. who dart by your car window, a sniffling runny-nosed baby strapped to their fragile bodies, joints protruding, right hand up with eyes begging for sympathy or alms—and you later find out, the baby is no kin and whatever is given goes to whoever hired them.

Vancouver, too, has a few dark spots like a stretch of Hastings St. by Chinatown. Once in a while, I’d stumble on a homeless man in a corner. A couple of them have taken a permanent post by the granite steps of the cathedral. I had talked to youngish woman I caught sniffling as she counted the coins thrown into a hanky she knotted in the corners as in a box, learning of an abusive husband she just left but tearing her heart out was a daughter too, she hoped to go back for once she recovered from the horror of that day. Didn’t I listen to a similar story of a woman who cradled the asthmatic child she fanned as it labored to breath through an uneasy slumber by the entrance of Harrison Plaza? Could poverty of hearts possibly incarnated into ghosts possibly haunting me, I had wondered then.

Ahhh..but there’s Manila Bay that overpowers with its irony of vastness, fullness even grandeur at its incomparable blaze at sunset. And for true-blue Manilenos, the romance of pocket corners in stonewalls and intimate streets scented by champaca, veiled in shivering shadows of ilang-ilang trees like those in Malate. I merely close my eyes to find my late husband sketching on his favorite dappled stone bench at Paco Cemetery, as he waited for me to finish up at the then Inquirer offices.

Like carrying a hidden side of the day moon, I stroll on Vancouver’s West End relishing shades of giant chestnut leaves, often pausing in a pergola by a formal English garden once a private estate, then promptly getting on to the end of the street on English Bay. Most times silky smooth unlike swollen Manila Bay, this bay unfurls at the feet as if cajoling in tiny wave rolls. Even its late summer sunsets are sweet peach orange, bouncing against slopes of mountains framing it as if it were a stage for dreams. Now, do I sound like I’m switching my affections? I think I’m two-timing!

Published at Business Mirror Philippines in my weekly column,

“Peregrine Notes”, August 5, 2012

Filed under: essay, opinion, thoughts | Tags: alegria imperial, alien, ancestral lot, Baclaran, business mirror, Canada, Ceferino M. 'Nonoy' Acosta III, funeral, generations, home, homing birds, impermeable, invisible, Manila, Ninoy Aquino International Airport, Paz Memorial Homes, peregrine notes, refelction, relatives, Roxas Blvd., The Little Prince, tide surge, unchanged, United Airlines

The word makes me wonder if most of us, like me, were born to leave home and later pine to return. Are we somehow reflections of homing birds, like the swallows of Capistrano, or the terns and geese of North America? Or closer to what I know, do we return where we come from like the salmon of British Columbia that swims back when matured to the river where it was spawned?

But unlike birds and fishes, home, for me, is no longer a place. I suppose it has ceased being one as I changed from one whom I recall even as recently as a year ago. This sense of being alien, which in a way is a reality, could have started to deepen like a whorl in my heart since six years ago when I hurriedly unloaded six decades of my life to live in Canada. At first, I couldn’t imagine going back home.

Where is home? Not that last apartment I emptied not only of accumulated debris but also of mementos and tags of moments lived, which my mother moved from house to house. Or an architect’s house that stood in an ancestral lot owned by five generations I was married into, which I had to sell. Where my sister and I lived with our parents for twenty years close to her high school is now a meaningless shell along smoggy Ramon Magsaysay Boulevard.

Not even where I was born already a vacant space shaded by an ageing pomelo by the time I learned how to read, the borrowed hut lent by an uncle of my father for my mother’s family driven into homelessness by WWII. Or where I grew up with my father’s mother said to be another temporary home built after their stone house from across was burnt. When my mother had to move back to her mother’s for care on the birth of my sister and my other grandmother debilitated with arthritis had to be hauled to a daughter in Manila, I watched it painfully torn down piece by piece and hoisted on to a carabao cart, with my childhood in it.

Massive convent walls where I was sent after high school and the dormitory run by nuns from across UST where I lived for six years sort of healed the gnawing loss I nursed from seeing those fragile walls just gone but I couldn’t call them home. Where then lies home? In my recent homecoming to Manila, I realized that home is both not a place and a structure but something “visible only to the heart” as The Little Prince of Antoine de Saint Exupery told the fox.

My homecoming last month was both ideal and deeply sad. Like a tide surge, my cousin’s death, Ceferino ‘Nonoy’ M. Acosta III, left no space for me to waver about a flight and waffle about gifts to bring. I was so wrapped up in my emotions that the smog, which swarmed the path of United Airlines on its descent to NAIA, failed to daunt me. Nor did the snarl in Baclaran, being a Wednesday, through Roxas Blvd. unnerve me. The landscape though felt shrunken and tighter with buildings now unfamiliar to me, and a crowd thrice multiplied; yet as the SUV that fetched me coughed through clogged streets, it had seemed normal.

I couldn’t guess how I would feel arriving at Paz Memorial Homes; it would be my first as a balikbayan. But with my first step into the chapel where Nonoy lay in state, I felt like I’ve been in it the day before—how many times have I bristled in the arctic air conditioning during a wake of relatives and friends? My uncle and aunt soon swept me in their grieving arms and we wept, sobbing words for the smiling Nonoy, a scene I have watched with other relatives countless of times.

When I turned to the faces riveted on us, there were my other uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces, nephews, relatives, and former neighbors sniveling with us. While most like me bore marks of time’s subtle scratches, each was whom I knew through the eyes—that invisible space impermeable to time, where I met theirs and my unchanged self.

We laughed, relishing not what was said but simply from the thrill of retrieving lost moments of being together. In the few days that followed, as we exchanged more of such moments–some with Nonoy in our midst–we kept flinging open the closed doors that had been shut by years. And as the burial crowd thinned out, when our clan gathered for what for me was yet another last time together, I had ceased to wonder if I have a home to go back to.

So like a homing bird and the salmon I had managed, indeed, with a tracker so precise scientists remain baffled, to land in or swim back to the same exact spot called, home. Yet unlike them, it’s not a spot I arrived at but a roof with walls I carry around unseen.

Published on January 6, 2013 Peregrine Notes, Opinion Page, Business Mirror Philippines

Photo: waders roosting at high tide in Roebuck Bay, Australia courtesy of wikipedia

Filed under: architecture, history, manifesto, news, opinion | Tags: 19th century, alegria imperial, concern, convento, Father Fidel Albano, Ilocos Norte, lease, Philippines, prominent, religious sisters, rumor, sacredness, San Nicolas, San Nicolas de Tolentino Catholic Church, Santa Rosa Academy, school, signifcance, SM, transpire

MANIFESTO

We, the undersigned Catholics of the Parish of San Nicolas de Tolentino and other concerned Catholics respectfully bring to Your Excellency our serious concern about the seemingly imminent lease or probably sale of a southern portion of the lot on which the Catholic Church stands. We only came to know this from some concerned Catholics of the town. Although we do not have a direct knowledge about this rumor, we are convinced it is true.

Visualizing what may happen next, this is the scenario we believe will transpire: that the southeastern portion of the Catholic lot immediately adjacent to the Catholic Church will be leased or maybe sold to SM, a giant commercial corporation that operates malls in different parts of the Philippines. How big the land to be leased is only a matter of our imagination but it could be the site of the convent and probably to include the eastern side of the original building of Santa Rosa Academy.

The size of the land rented or leased whether small or big is not important to us. What concerns us is the desecration of a sacred ground and the invasion of the privacy of our Catholic Church and Sta. Rosa Academy considering the fact that the commercial building will be built just beside the Catholic Church on its southern side and adjacent to the old building of Sta. Rosa Academy on its eastern side.

Please note Your Excellency, that the said place to be leased constitutes the most prominent portion of the lot of the Catholic Church. It is, to us, of sacred significance. The prominent location of the place is the reason why Father Fidel Albano, a parish priest of San Nicolas, selected the place as the site of the present convent. That was in the twilight of the 19th century. The construction of the present convento was necessary after Father Fidel Albano handed the old convento (now the main building of Sta. Rosa Academy) to the religious sisters who were asked to administer the school.

The present convento was constructed by the Catholics of San Nicolas under the leadership of the parish priest, Father Fidel Albano. We object to its being torn down and relocated.

True, renting the site of the convento and some buildings of sta. Rosa Academy on its eastern side will generate millions of pesos in revenue. But for what purpose? And at what expense? Will the end justify the means? Does the Catholic Church of San Nicolas, which comprise the Catholics of the town, need that money badly? Is the revenue of the church as of now failing so badly? On the contrary, the revenue of the church is sound. It is good!

It is worthy to note that while a house of worship and a school should be insulated from the material world, at San Nicolas a design is in the making to define the sacredness of the church by building, a mall just beside it and pollute its spiritual atmosphere with materialism. The presence of the mall just beside Sta. Rosa Academy will destroy its academic dignity. This will scandalize us, the Catholic faithful.

Relative to the operation of a mall, just beside the church, we are reminded of the scene when Jesus witnessed repulsive materialism that corrupted a church of god (temple). He saw people making money right in the temple of God, and in anger, He protested and cried aloud, “Take those things (referring to the objects sold in the temple) and do not make the house of my Father a house of business.” (John 2:16). Is not placing a mall for the sake of money, just beside the church a desecration of the church of God?

At Laoag City business establishments are indeed located around the Cathedral and this situation maybe used as justification for the building and operation of the mall beside the church of San Nicolas. However, the situation at the Cathedral of Laoag and the Church of San Nicolas are two very different things. The business establishments such as Chowking, Jollibee, McDonald’s etc operating on land owned by the Cathedral are at a decent distance from the church. At San Nicolas, SM will be sitting just beside the Catholic Church. The very thought of it is not only shocking but obnoxious and repulsive to the decency of the concerned Catholics of San Nicolas.

The undersigned would have no opposition to a mall built on the church property on the vacant lot north of the church as long as it is built at least at a decent distance of about 30 meters away from the northern wall of the Catholic Church. The Catholics of San Nicolas however desire transparency and involvement in the project itself.

In case the needs of the church for repairs is made as an excuse for the lease. Throughout the centuries when the church was destroyed by typhoon, fires and earthquakes, the Catholics of the town were forthcoming in producing the funds for such repairs.

In the construction of the floor of the church and other projects, did not the Catholics of San Nicolas (with help from other people) make the projects a reality? No less than Father Danny Laeda said so during the closing ceremony at the Plaza during the feast of Christ the King on November 2010. Therefore, there is no need to lease the site of the present convent and its surroundings to SM just to produce money.

Premises considered the undersigned and all other Catholics who may not have signed this Manifesto but support its cause voice their strong objection to the lease of the lot where the present convent stands and adjoining lots. They strongly oppose the transfer of the convent to the lot north of the Church.

Truly yours in Christ:

Ma. Cielito Valdes-Lejano (Quezon City, Philippines)

Leonardo B. Lejano (Quezon City, Philippines)

Alegria Albano-Imperial (Vancouver, Canada, formerly of Bacarra, Ilocos Norte and Manila)

Elizabeth Medina (Chile)–granddaughter of the late

Gov. Emilio Ortega Medina of Dingras, Ilocos Norte

Victoria Rosario Albano (Vancouver, Canada, formerly of Bacarra, Ilocos Norte)

If you support this ‘plea’, you may want to add your name in this manifesto by leaving it as a comment and I’ll add it here.

Dios ti agngina ken sapay koma ta denggen ti Apo daytoy a dawat tayo.

Also posted at http://www.iluko.com

Filed under: essay, language | Tags: alegria imperial, English, essay, filipineses09, Iluko, iluko.com, riddle

Uggor na ti lubong. Awan biag dagiti darikmat no saanda nga aglasat iti bitekna. Kas anniniwan ti agdaliasat nga aldaw no saanna nga marikna ti agek ti parbangon, arakup ti malem, no saanna a mangeg ti arasaas dagiti bituen, duayya ti rabii. Kaingingas ti papel dagiti sabong no saanna ida taliawen, no sanna nga aprosan ti sim-meda nga isemda, no saanna nga ikidem nga sul-uyen ti bangloda.

Uray dumanarudor dagiti bambantay no mariingda, awan kaipapanna no saanna nga madlaw ti sakit ti nakemda. Uray di agpatingga ti ririaw dagiti riniwriwriw a bulbulong ti kawayan awan makaawat kadagiti ananek-ekenda no saanna nga ipalubos ti kabagi-anna nga mangnga-asi.

Anianto payen no saan nga matokar ti maysa a timek ti bitekna, no saan nga agbaliw ti widawidna a kas awan mangmangegna, timek a mangal-allukoy, sam-it nga agayus iti sanguannanna. Agsawisiw ti angin, agsenna-ay dagiti pakak a metektkan nga agur-uray ti isungbatna.

Masangpetanna ti sabangan nga maang-san. No saanna a maikaso nga isang-at dagiti ladladingit daytoy, malnekanton nga agsansaning-i dagiti dalluyon . Nupay agguilap-guilap ti masipngetan a waig awan pategna no saan a maaawis dagiti bitekna ket babaen ti mata a mangmingming kadagiti darepdep dagiti bituen.

Iggemna ti napalabas. Agbibiag iti masukunsukot a silidna, silid nga awan ridiridaw. Petpetna ti agdama. Nalukay unay nga kumaradap daytoy kadagiti agsisillapid a dalan iti kaungganna, dagiti rinibribu a pagayusan ti rikna. Padpadaananna ti masanguanna, dagiti darepdep nga agam-ampayag nga ilillili ti bulan ket no saanna nga sippawen dagitoy, matnagda kas bato iti kumkumraang a kapanagan.

Awan masao a bukelna. Maysa laeng daytoy a kas prasko, awan nagyan, awan aglasat kaniana ket agbayag. Masapul nga bayat bitekna maiwerret dagiti pampanunot, rikriknaen, sasao, an-anek-ek, dardarepdep a bibiagen dagiti bituen.

Uggorna ti ayat. Ngem awan makatiliw, makapugto no ania ti kita daytoy, no ayanna ti nangitukelanna, ayanna ti pangsibsibuganna. Uray no kasano ti gagar dagiti agsisiim iti parbangon, wenno tengga’t aldaw, wenno iti panagkeppet ti langit a makatiliw ti daytoy kapatgan nga uggorna, a ti lubong ti kaibatoganna, mapaayda.

Mapaayda urayaman no pirpirsayenda. Uggorna ti lubong dagiti agayan-ayat, lubong nga ubbog ti biag, lubong a kadakdakkel wenno kabasbassit ti gemgem, ket kas gemgem awan matiliw, awan masirip a nagyan, kas rikna.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Alegria Imperial

Posted in iluko.com 02/14/2010